In the 1980s Noddy came to Burnie and the beginning of a grassroots art movement formed, marked by multi-artform experimentation and zines. The Big Ears Club was an anarchic evening of cabaret, post-punk music, zines, eyeliner and bleached hair founded by Scott Rankin, Andrew Viney and other young people, which went on to inspire the beginnings of Big hART.

“It was a simple way of giving people a voice. I think that was what it was for us. Because you’re young you don’t have a voice. It was us having a bit of a scream into small town conservatism” – Andrew Viney.

The thread of zines runs in Big hART’s veins, but it began before Big hART, back in 1980s Burnie, at a place for young people called The Big Ears Club. A lanky, young, 18-year-old called Scott Rankin had just arrived in town. The ideas that the Big Ears Club experimented with became the DNA of what Big hART is today.

Andrew Viney, now Big hART’s National Program Manager and the Producer of Acoustic Life of Sheds grew up in Burnie and was one of the original founders of the Big Ears Club. “We were just some musicians wanting to do original music and doing it yourself was more important than music abilities”, says Andrew Viney, “I said to Scott, ‘Oh, we should do it, have a club and do stuff in Burnie’, and he said ‘Ok we’ll do it’. I didn’t mean we actually do it.”

Noddy’s Revenge performs at the Big Ears Club, Burnie Hotel. Far Left Scott Rankin, Harvey Saward on guitar, Graham Rankin on drums, Andrew Viney on bass at far right. Photo Courtesy Karyn Hannah.

They were inspired by little known Scottish bands – Aztec Camera, Orange Juice and Josef K. There was also a cannon of bands that the young people listened to – Velvet Underground, Sex Pistols, Talking Heads.

“Scott Rankin had just turned up from Sydney. I don’t think he knew anything about underground music, but he seemed to know about other sorts of music that we had no idea about. He was already doing a kind of cabaret musical thing to help support himself in Burnie. He’d play 1930s jazz standards in his cabaret show.”

They started their new club at the Burnie Hotel (now the Green’s Hotel), the pub which only the wharfies drank at.

“It was the rundown pub on the docks and nobody, no young person would ever think of going there, but we got the dining room and the kitchen” says Scott Rankin. “I used to live upstairs in a converted bit of hotel where Errol Flynn once stayed.”

Scott Rankin & Harvey Saward (left). Scott MC-ing at Big Ears Club (right). Photos Courtesy Di Saward & Karyn Hannah.

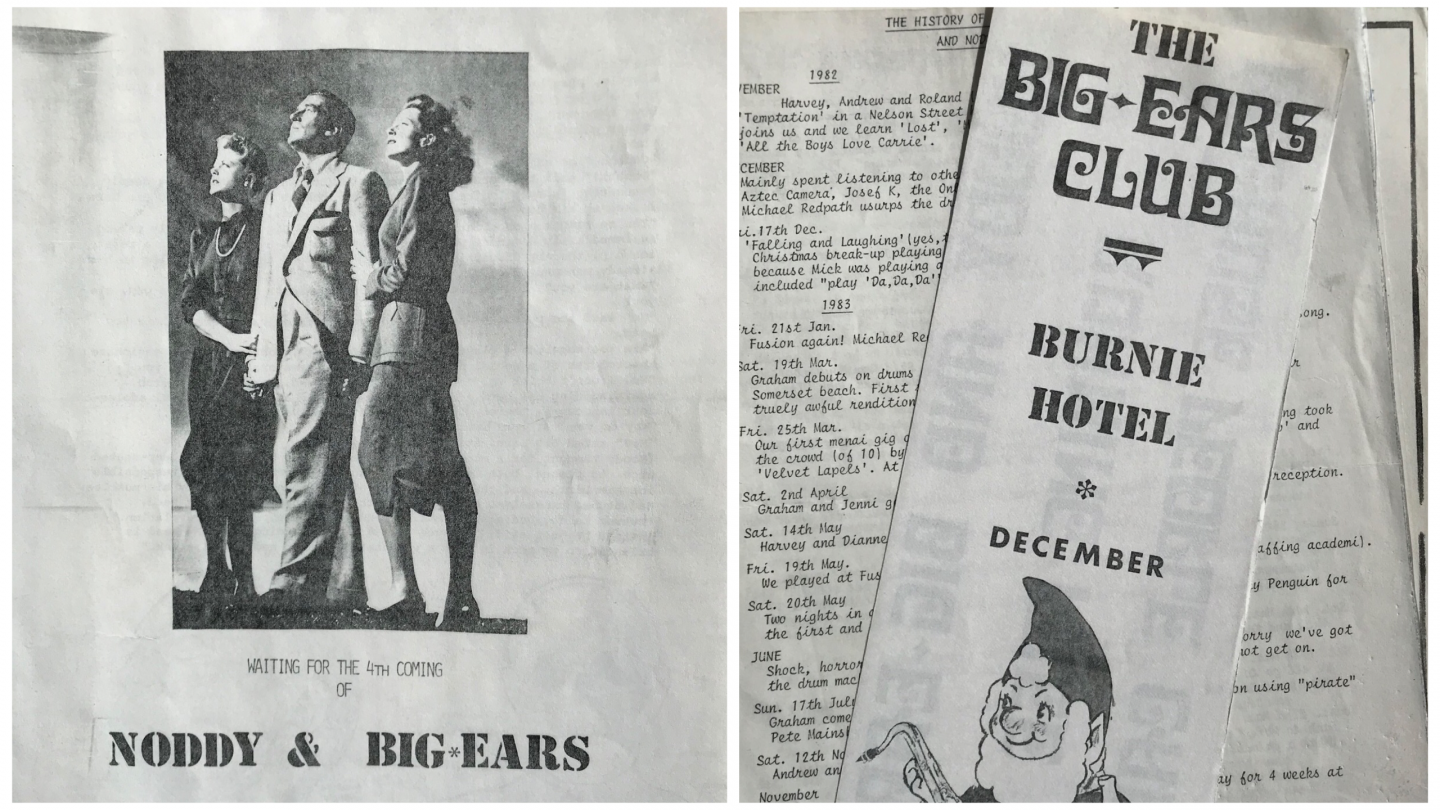

The title of the club took its name from the tales of Noddy, Enid Blyton’s popular children’s book series. Big Ears is the wise and friendly gnome who often rescues Noddy from peril, and also has the power to cast spells. The series was called into question by the powers-at-be for its literary merits and whether the imaginary land of Toy Town with its slapstick violence, and undercurrent themes of racism, sexism, and homoeroticism was indeed appropriate for the minds of children.

“It began initially as a facetious thing because Noddy and Big Ears was being banned from libraries and schools”, says Scott Rankin. “We used the phrase ‘Noddy and Big Ears Running Free Because People Care’, which was a parody of the Gordon Franklin running free because people care”.

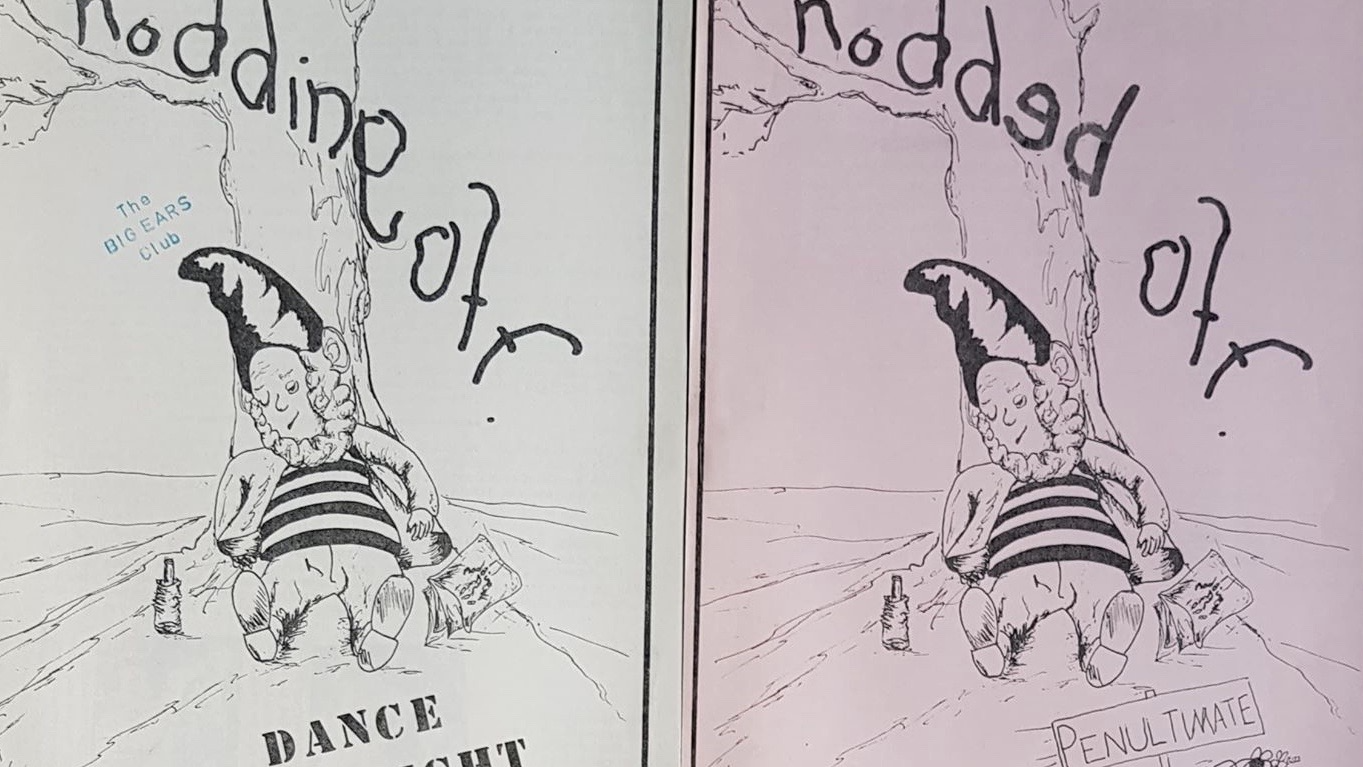

Front Covers of the Big Ears Club Fanzine. Courtesy Di Saward.

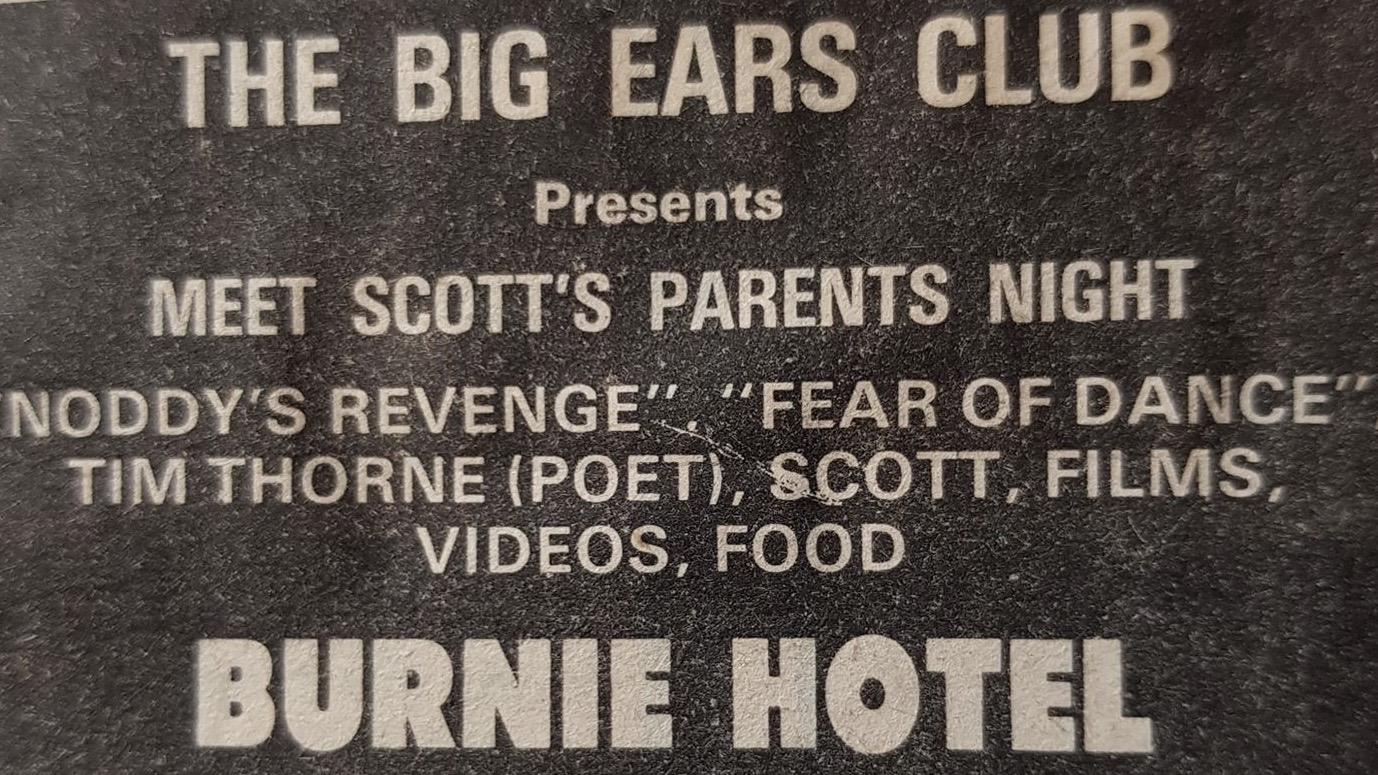

Andrew’s band, ‘Noddy’s Revenge’, became the house-band for the club, with Harvey Saward on vocals and guitar, Mick Anderson on guitar, Graham Rankin on drums, 16-year-old Mitchell Cross on saxophone, and Andrew Viney on bass. Scott was the MC and performed cabaret vignettes, including one where, legend has it, he ate a huge amount of caramello chocolate and spewed it out onstage. Each week they produced a zine of poetry, recipes and ideas which was handed out to everyone who came to the club. The other band who featured was Fear of Dance, “who had a drum machine, so they were more alternative than us”, says Andrew tongue-in-cheek.

So what was the Big Ears Club like? “There was a fair bit of eyeliner and bleached hair, it was just part of the post-punk thing. All young people want to push against the norm”, says Andrew. “Our friend Ted from Fear of Dance wore bondage pants and moved from Devonport to Burnie because in Burnie they’d just laugh at you, but in Devonport they’d want to beat you up.”

Newspaper Clippings from the Big Ears Club. Scott Rankin left and music review right. Courtesy Di Saward.

They wore pointy shoes, thin ties and big coats and the girls’ fashion was influenced by the 60s mods. “You’d never re-create the kind of hipness and daggyness, and youthful enthusiasm”, says Andrew.

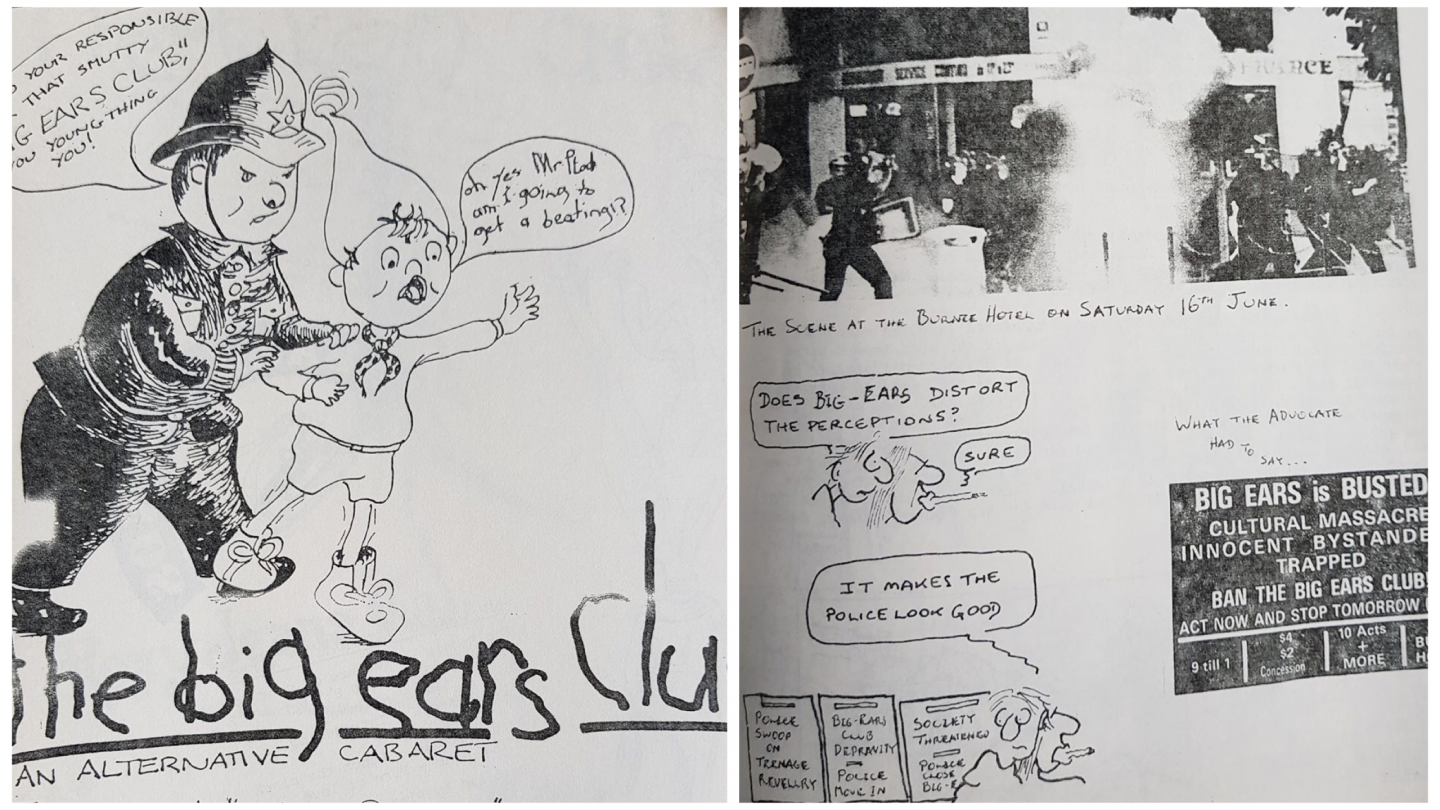

“A lot of underage kids started coming to the club, we were raided a couple of times”, recalls Scott Rankin. “On one occasion I hid kids upstairs in my apartment, it was good fun.”

“We would serve cakes. There were some political things, it was the time when there were blockades at the Pulp. We weren’t actively lobbying, just making lots of different forms of art at the same time.”

Zine cover left, Big Ears archival materials. Courtesy: Di Saward & Karyn Hannah.

The zine was produced out of the offices of the Adult Education Centre, which was run by an old anarchist, where Andrew worked as a clerk. It was the days when shiny new photocopiers were transforming workplaces. Andrew, Scott and the crew would be madly putting the zine together the day before club night – printing and double-siding copy manually, stapling and printing reams of paper. They were inspired by Sniffin’ Glue, which is viewed as the first punk fanzine, produced by Mark Perry in 1976 after seeing The Ramones.

“It was all very anarchic. It was kind of anyone who had anything to put in, there was no rules, censorship or creative control”, says Andrew. “Then there was Scott’s continuing stories about Noddy and Big Ears, which had a bit of obscenity. It was people kicking against the local culture, making fun of it.”

The Big Ears Club was raided several times. Cartoons & graphics from the Zine. Courtesy: Di Saward.

“There was some hate mail from Christians, because the area’s fairly conservative. We were doing the devil’s work.”

Scott Rankin says that the main point about the zine was the speed in which they produced material. “It was super rough and ready and had its own feel. We’d just write stuff and steal stuff – poetry, recipes, ideas, madness and illustrations. We’d do one every week for the season, and you’d get it when you came to the club. That was the start of zines and that was 10 years before Big hART.”

The hybrid, multi-arts focus of the Big Ears Club would influence Scott Rankin in his later work and in the projects of Big hART, with the zines becoming a continual creative through line in Big hART’s work all the way to the present.

“It was an exciting time. It was the kind of thing you might come across in inner city Melbourne, so it was radical”, remembers Andrew Viney.

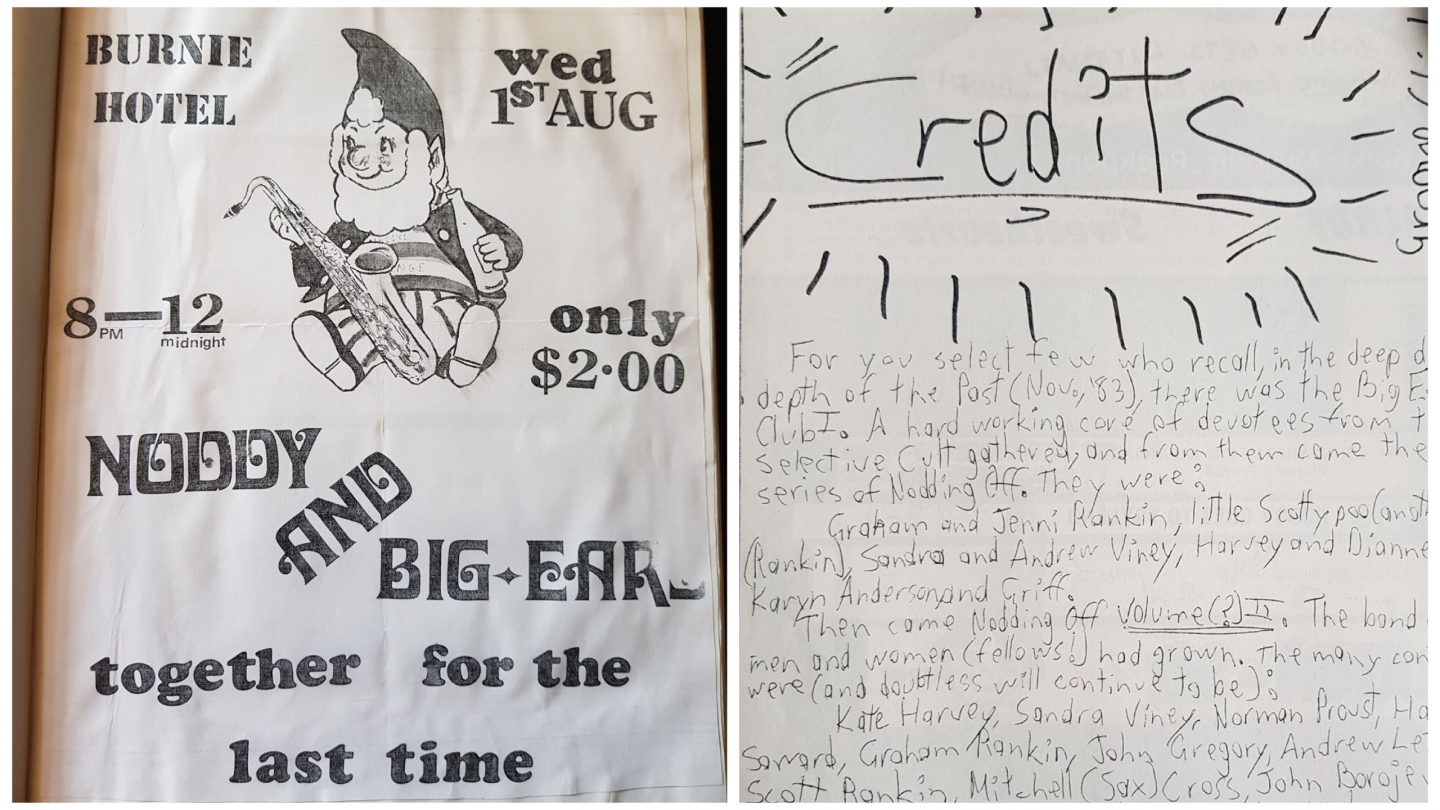

Advertising for the Big Ears Club. Courtesy: Di Saward.

“We had poets, jazz, and teenage punks from Launceston came and played. We had Tim Thorne the poet perform, a completely different audience for him. I think he went away thinking ‘that was weird, how could this be happening in Burnie?’”

“The beauty of a small town is that no one’s going do it for you. If you want something to happen, you’ve got to do it yourself” says Andrew. “That still remains a strength for regional towns. You can either leave; or create what it is that you want, where you are.”

Young people of Project O are now working on a national digital zine led by Big hART’s Associate Director Genevieve Dugard, working with designer Jes Hoskin, digital illustrator and animator Maeve Baker, filmmaker Nicky Akehurst, sound artist Leith Alexander and designer Monica Higgins. Young people are exploring digital illustration, animation, film and audio stories to create a new mode of self-expression for the 21st Century.

Digital Illustration by Eli of Project O Frankston, supported by mentors Maeve Baker, Jes Hoskin & Maggie Abraham.

“What we’re doing now is very polished in fanzine land, but what we were doing then was very anarchic and raw” says Scott Rankin. “But we’re still using similar notions, aspects of youth culture.”

“Scott was definitely developing the ideas then” says Andrew. “The idea that you experiment, and that if something fails it doesn’t matter. You say yes, you give it a go, and you learn from it.”

Final poster for the Big Ears Club and zine credits. Courtesy: Karyn Hannah & Di Saward.

Article by Bettina Richter, with thanks to Andrew Viney, Scott Rankin, Di Saward & Karyn Hannah.