A chance encounter for Big hART's Roebourne Producer Aimee Kepa with the Brazilian artform capoeira in Adelaide, led to a lifelong fascination. This practice of collective strength and resistance took her to London and Lebanon, and she's now using it to build confidence with young women and female inmates in Roebourne.

“If we can move in different ways, we can also think in different ways”, says Aimee Kepa in this first-person piece, “The way I approach capoeira workshops in Roebourne – with young women and women in the prison – is you’re building physical strength, coordination and flexibility, but you’re also building a certain level of resilience.”

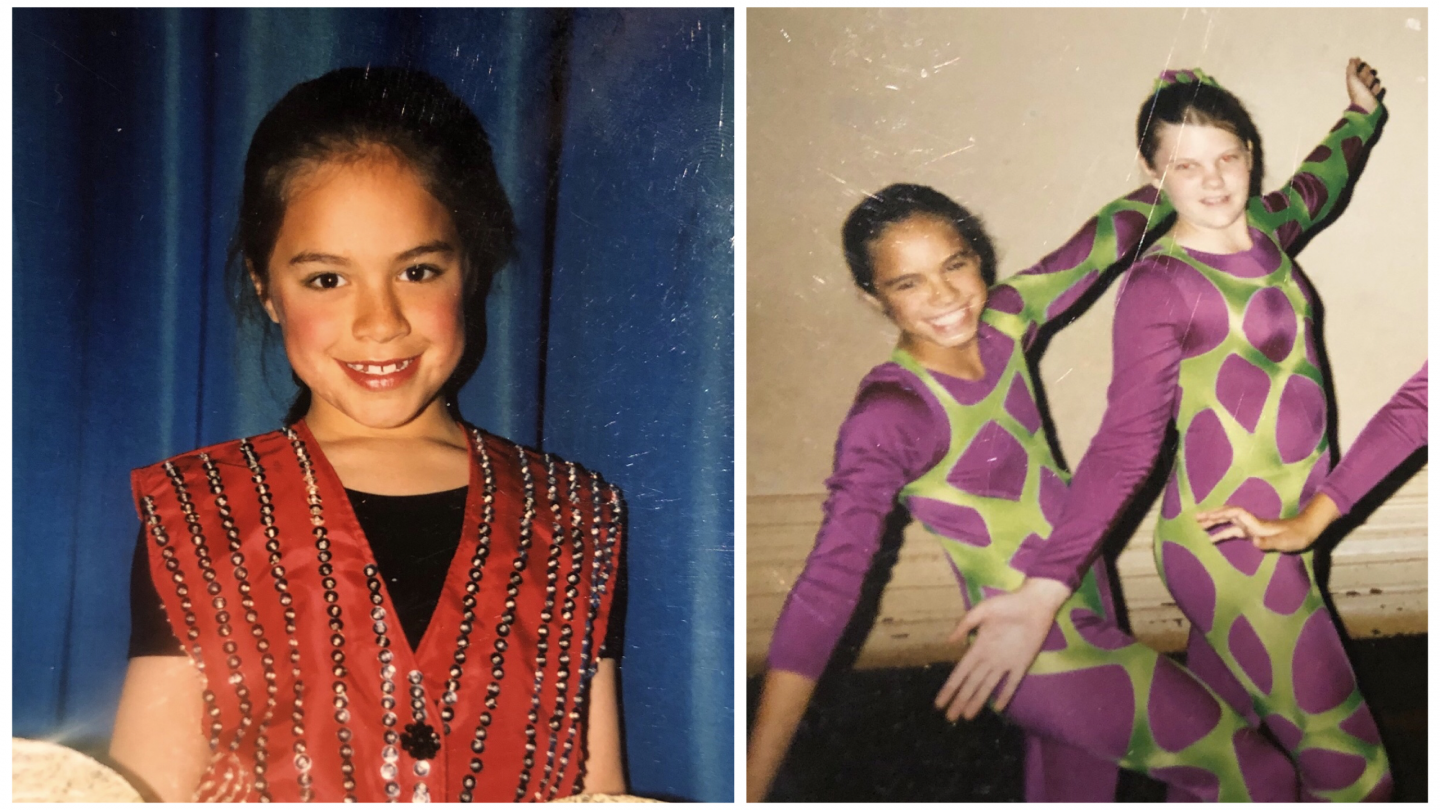

I always danced. As a little girl I did ballet and contemporary dance, starting when I was five-years-old I went through what options there were living in regional South Australia.

Aimee danced from the age of 5-years-old. Photo: Supplied.

When I moved to Adelaide for high school I was first exposed to capoeira and it really captured my imagination. I remember going along to the first class, there was this amazing music, really percussive. People were doing acrobatics, there was martial arts as well as dance, then singing at the end of the class. I was intrigued. What first struck me was this strong community of people that were all involved in this practice. I was looking for something with more of an edge, and it triggered a lifelong obsession.

A chance encouter with capoeira triggered a lifelong obsession for Aimee Kepa. Photo: Supplied

A history of resistance

As I’ve learned more of the movement, I’ve learnt about the history and how capoeira evolved from a very complex situation. Capoeira is an active resistance, you’ve got these elements of fight and play. It was developed by the African slaves, predominantly from Angola, who had been brought to Brazil by the Portuguese, emerging as a way for them to subversively practice elements of their culture and religion, Candomblé. They disguised their worship and fight as a dance, speaking to their gods by using pseudonyms of Catholic saints to appease the Portuguese slave drivers and it gave them a lot of strength.

Elements of fight and play, Aimee performing capoeira. Photo: Supplied

Capoeira evolved to being something that was outlawed for a long time, it went underground and onto the streets. Then there came this interesting period where Brazil was trying to push a national identity and capoeira went from being this subversive active resistance to being a celebrated, national Afro Brazilian artform and cultural practice.

The community of capoeira

Growing up, capoeira in Adelaide attracted quite different people, and I really enjoyed being part of that community. I had a lot of opportunities – I was able to travel, teach capoeira around Australia to remote Aboriginal communities, perform overseas and travel to Brazil to train.

As a 19-year-old being able to go to Brazil, capoeira was an entry point to sharing in a culture. If you have capoeira, you can go to a new community, go to different schools, you have this shared language and you’re able to become part of a new community.

The community of capoeira – Aimee in action. Photo: Supplied

Movement pathways

I never stopped doing capoeira or Afro Brazilian dances that are associated with capoeira. After I finished university, I was working as a lawyer but I was still so interested in the potential of capoeira, so I moved to London so that I could pursue a Master’s in Dance Anthropology. I was able to look more closely at my own experiences of capoeira- investigating, interrogating the idea of how identity is something that can be physically embodied. When we do movement, we’re involved in particular kinds of practices which can impact how we move through society, and the types of communities that we become a part of.

Aimee Kepa with Choreographer Wayne McGregor. Photo: Wendell Teodoro

Then there was an opportunity to work with choreographer Wayne McGregor, a leading British choreographer and incredible artist with a great intellect. Part of his practice was around the idea that creativity is not intuitive, it’s something that can be nurtured. He had worked with anthropologists and neuroscientists who were researching depression, looking at how you could cultivate new neural pathways through the body, and how movement can trigger different cognitive responses. If we can move in different ways, we can also think in different ways. Having grown up in Adelaide to then be working with this leading choreographer in London was amazing. All of a sudden I was part of this incredible artistic world.

Working with young women in Roebourne

Leshonrae, Billiesha and Bella warming up for capoeira class in Roebourne with Aimee Kepa. Photo: Big hART

Part of the idea of the workshops, particularly for young women, is about building confidence for them to take up physical space. That’s about not being shamed, not being shy, and not being too self-conscious either. The way I approach capoeira workshops in Roebourne is you’re building physical strength, coordination and flexibility, but you’re also building a certain level of resilience.

Leshonrae and Bella trying out some capoeira moves, Roebourne. Photo: Big hART

We try to provide different kinds of opportunities for them to step out of their comfort zones and to be proud of themselves as well.

In the prison

My experience of the women in prison is they don’t have a great amount of confidence, some of them feel like they’re letting down a lot of people, so my goal is just to show them a different side to themselves.

Capoeira workshops are happening in the prison. Photo: Spark Post

There’s always something that people can draw from capoeira. Whether it’s the music, the percussion or it might be the acrobatics – being able to practice handstands; or this idea of the fight, the kicking and the tripping. Sometimes we just sit down and play instruments, it’s about sharing that energy and having fun. The dance stuff has been really good, for example, I’m just getting them shaking their bums at the moment!

Building agency

Underlying it all is building physical strength and confidence. The great thing about capoeira is that it happens as a collective, and you’re pushed out of your comfort zone, but you’re being supported by everyone else at the same time.

Capoeira is collective and you support each other. Warming up in Roebourne. Photo: Big hART

The women in the prison that I work with, they’re not being judged, they’re being supported by their peers. For these women it’s a really strong practice because of the history, how it was created out of an act of resistance, as a way of taking control over situations. I think it’s great for building agency in the young people, and the women in prison. For them to say, ‘I can do these things’, ‘I can try new things and it makes me feel good’.

Amareisha learning percussion with Aimee, Roebourne. Photo: Big hART

Coming full circle

I’ve kind of come full circle. I taught in juvenile detention centres when I was nineteen and twenty, we would go in and work with these young boys. I’m now 34 and I’m back in the prison, but I’m working with adult women, it’s really nice. I feel very privileged that I’m in a position where I can share something small with these ladies. The women that are inside they’re carrying so much, all these different layers of responsibility, and guilt that they’re feeling, sometimes the self-hatred is palpable. What I really like about teaching movement workshops is that they forget about that for a moment.

Aimee with young women in Roebourne. Photo Credit: Chenise

To find out more about Big hART’s New Roebourne projects, visit our website: https://newroebourne.bighart.org

Interview with Aimee Kepa, Edited by Bettina Richter